In this edition of WGG’s1IWRAW Asia Pacific has been a consortium lead of the Women Gaining Ground (WGG) project in partnership with CREA and Akili Dada since 2021. WGG is being implemented in collaboration with 16 in-country partners (in Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda), focusing on addressing gender-based violence (GBV) and increasing the leadership of young women and women with disabilities. monthly blog series, Hameeda Syed, WGG Fellow, unpacks the phenomenon of surveillance, beyond and within the digital realm, as a feminist issue and why do feminists need to engage and critically problematise surveillance as a tool of power, control and oppression.

As a citizen, who gets seen, who gets ignored, and who pays the price for being watched?

Qandeel Baloch, a Pakistani influencer lived a life under intense social surveillance. Her use of social media offered her a platform to express herself, challenge norms, and build a public persona. But this same visibility made her a target for scrutiny. Her family, and wider society, reacted with condemnation, viewing her actions as a threat to traditional values. Her life, and online activity, were constantly observed, judged, and ultimately, this surveillance, fueled by patriarchal structures, led to her murder.

The anxieties and its manifestations are not isolated incidents. Through platforms and devices, they are a symbol of the tension between progress and the desire to maintain the status quo. They are reflections of a system of scrutiny or surveillance that goes beyond family dynamics into the very fabric of power. They spark curiosity towards a larger, more political question:

Who, in any society, is truly allowed to move freely, speak openly, and simply exist without any scrutiny?

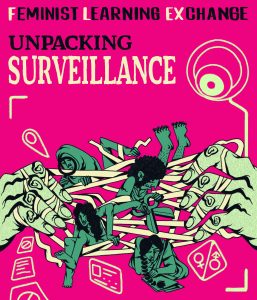

This was one of the questions and systems that the participants at the Feminist Learning Exchange (FLEX) 3.0 workshop–hosted by IWRAW Asia Pacific–aimed to understand. Young feminist leaders from across Africa and Asia explored the topic of surveillance as a system of power used by the state to shape society, categorise people, and control behavior.

IWRAW Asia Pacific and the participants of FLEX 3.0 which took place from 12 – 14 February 2025, in Phuket, Thailand.

Surveillance dictates who is seen and who isn’t, manipulating people into policing themselves and each other, often in the service of the state’s agenda of maintaining its status quo.

Who is erased and targeted by this constant watching? Those already marginalised and those who challenge the state. Surveillance shapes the imagination of what a perfect body should look like, as seen in how women with non-normative appearances (looking ‘tomboyish’), queer and disabled individuals face medical profiling and social ridicule. It also controls who should be allowed to exist in public spaces and practice leisure, especially under regimes that monitor activism. Finally, surveillance intrudes in the private sphere, where everyday digital actions of minorities across gender, religion, ethnicity, race and class leaves them vulnerable to monitoring, turning even rest into a site of risk.

This structure is replicated in digital realities. The increasing use of new technologies by the state to collect data for the purpose of tracking behaviors and actions reinforce existing power structures, creating a climate of fear and self-censorship. As workshop participants discussed, this can lead to people policing themselves and their communities, internalising the state’s gaze and building a psychological reality of the Panopticon.

Originally conceived by utilitarian scholar Jeremy Bentham, the Panopticon is a circular building having holding cells with a watch tower at the centre. Through the visual, Bentham’s focus was highlighting the nature of unseen surveillance. French philosopher Michel Foucault took it a step further, seeing it as a metaphor for the mechanisms of power in modern society. He believed the Panopticon was effective in internalising the sense of ‘being watched’, leading to self-discipline.

So, under the Panoptic gaze, individuals, influenced by the state’s perceived norms, begin to police their own actions and those of their communities, effectively serving as extensions of the state’s surveillance apparatus. Who ultimately pays the price for this? With the expansion of surveillance in previously unknown forms, the boundaries between private and public have blurred. Surveillance has evolved into a tool to predict and control our future actions. Governments and corporations, often working together, collect vast amounts of our data to try to anticipate our behavior. This “surveillance capitalism” transforms our lives into commodities or data points that can be sold and used by the state and other powerful actors to suppress dissent, manipulate elections, and limit our fundamental rights. At the workshop, participants explored how surveillance, often driven by the state, becomes a part of our lives under the veil of convenience.

If surveillance is fundamentally about the exercise of state power, then resisting it becomes a political and feminist act. Feminist politics challenge power that restrict choice and refuse systems that marginalise, surveil, and silence the right of choice to exist.

Participants, discussing strategies for resistance, shared about developing new secure digital behaviors to counter surveillance, such as using encryption to protect data, and being more selective about what information is shared online. They also pushed for building stronger movements through organising, educating the public, and mobilising communities to challenge surveillance practices and advocate for policy changes. For instance, they suggested anonymity as a strategy to mobilise politically on social media to evade online surveillance. Creating safe spaces for collective care and support was key to creating spaces resistant to surveillance and self-censorship, where alternative narratives could be shared and harmful norms challenged.

The participants stressed the need for collective political action to dismantle and reimagine the systems that enable state surveillance. Feminist organising and activism are frequent targets of state surveillance, with laws being strategically used to suppress feminist and human rights movements. So, feminist movements must build resilience and develop counter-strategies to protect themselves from state surveillance. The goal goes beyond evading the manifestations of state surveillance into fundamentally dismantling the structures that enable surveillance to exist in the first place.

But there are challenges to building this utopia. States possess superior resources, including financial, technological, and legal instruments, compared to most feminist movements. This creates an asymmetrical power dynamic that makes it extremely difficult to dismantle their surveillance structures.

The other reality is that feminist movements are not homogenous. They hold multiple ideologies, priorities, and lived experiences. Reaching a consensus on effective counter-strategies and maintaining internal cohesion in the face of state pressure can be challenging.

In between all of these musings, as feminists, to engage with surveillance is to engage directly with the mechanisms of state power. It makes us think: Who is being watched by the state? Who is being protected by the state? Who is being targeted by the state?

Official illustration of FLEX 3.0 designed by Mia Jose, depicting the invisible hands manipulating forces of power in a surveillance state and all of those, especially marginalised women, whom are entangled within it.

Surveillance becomes a choice exercised by the state to decide who gets to live freely and who doesn’t.

Feminists must confront surveillance not just as a privacy issue, but as a tool the state uses to control our freedom, our ability to be seen and heard, and our fundamental rights. The most effective form of surveillance is the most invisible, normalised through policies, cultural narratives, technology, and self-censorship.

Let’s come back to Qandeel’s life. What do we see? Through societal norms and familial anxieties, the system attempted to control her expression and autonomy, mirroring the broader mechanisms of state surveillance. To resist this, to demand the right to exist free from control and interference is what the fight for feminism, at its core, is all about: challenging and dismantling unaccountable power.

____________

Hameeda Syed (they/she) is a journalist, gender consultant, and co-founder of Dignity in Difference (DiD), an organization resisting digital violence through tools, research, and advocacy in South Asia. At DiD, they head programs and partnerships centering on and enhancing the experiences of minority communities in online spaces through narrative change. They are based in New Delhi, India.

Footnotes

- 1IWRAW Asia Pacific has been a consortium lead of the Women Gaining Ground (WGG) project in partnership with CREA and Akili Dada since 2021. WGG is being implemented in collaboration with 16 in-country partners (in Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda), focusing on addressing gender-based violence (GBV) and increasing the leadership of young women and women with disabilities.