Gender budgeting

Gender budgeting  The COVID-19 pandemic, macroeconomy and women

The COVID-19 pandemic, macroeconomy and women

A purple economy

The world runs on/because of care work.1As we have discussed and illustrated in the previous sections of this starter kit, care work for families, communities, and the natural world (which is largely undertaken by women due to stereotypical gender roles) is essential to our wellbeing and continuity of life as we know it on this planet. However, the current dominant economic structures and approaches rely on the devaluation of care, as well as a general undervaluation of work typically performed by women. These patterns of devaluation enable the economy to continue in its exploitative state. A good resource that explains these is WomanKind’s Working Towards a Feminist Just Economy: https://world-psi.org/uncsw/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ working-towards-a-just-feminist-economy-final-web.pdf Yet, as we have discussed throughout the starter kit, care work is not sufficiently recognised, valued, and redistributed to ensure that women are not burdened by it. With this in mind, feminist economist Professor İpek İlkkaracan has coined the term ‘purple economy’ and formulated an economic framework that recognises the vitality of care work in all aspects of life. It also recognises the disadvantages women face due to the stereotyped burden of unpaid care forced onto them by society, such as the employment gap, gender wage gap, and job segregation.

The world runs on/because of care work.1As we have discussed and illustrated in the previous sections of this starter kit, care work for families, communities, and the natural world (which is largely undertaken by women due to stereotypical gender roles) is essential to our wellbeing and continuity of life as we know it on this planet. However, the current dominant economic structures and approaches rely on the devaluation of care, as well as a general undervaluation of work typically performed by women. These patterns of devaluation enable the economy to continue in its exploitative state. A good resource that explains these is WomanKind’s Working Towards a Feminist Just Economy: https://world-psi.org/uncsw/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ working-towards-a-just-feminist-economy-final-web.pdf Yet, as we have discussed throughout the starter kit, care work is not sufficiently recognised, valued, and redistributed to ensure that women are not burdened by it. With this in mind, feminist economist Professor İpek İlkkaracan has coined the term ‘purple economy’ and formulated an economic framework that recognises the vitality of care work in all aspects of life. It also recognises the disadvantages women face due to the stereotyped burden of unpaid care forced onto them by society, such as the employment gap, gender wage gap, and job segregation.

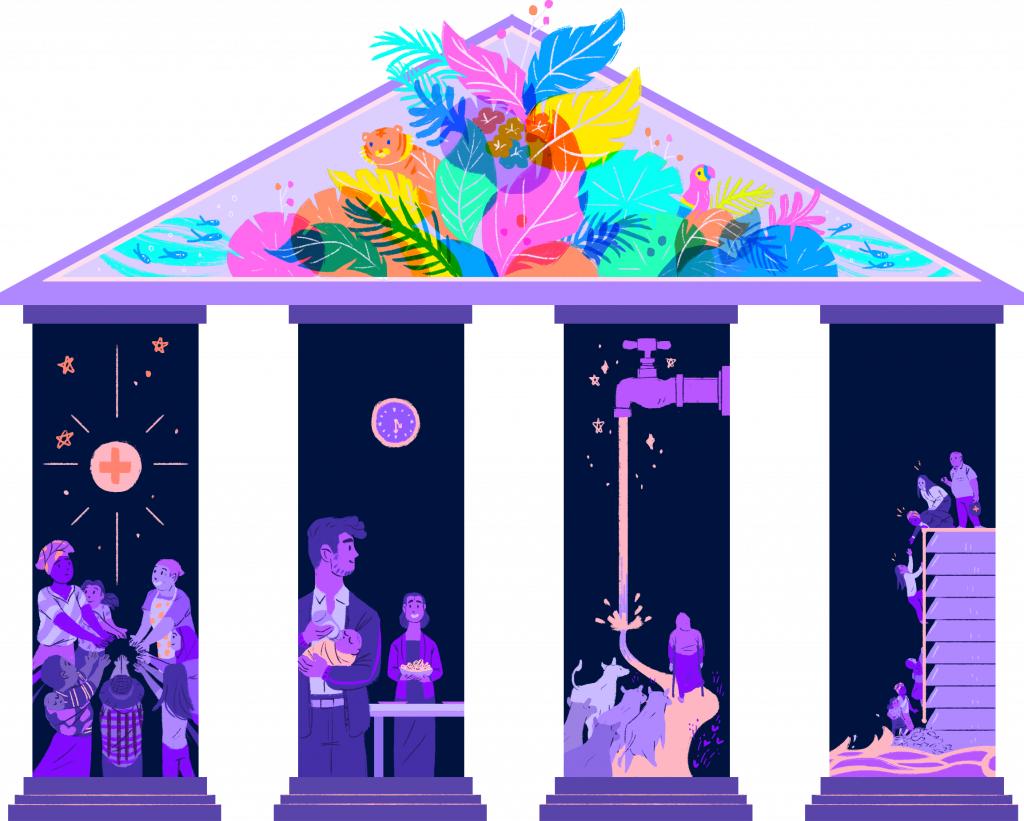

There are four pillars of the purple economy:

- A universal infrastructure of social care services: The lack of access to care services becomes an issue of both gender and class because professional care services can only be accessed by those in higher-income households. In order to ensure that all households are able to access professional care services, either public care services or private care services subsidised by the state should be present and accessible by all.

- Regulation of the labour market for work-life balance: This includes measures for redistributing the burden of care work more equally between women and men (paternity and parental leaves, etc.), as well as measures to ensure that these care responsibilities can be undertaken by all genders (such as shorter working hours, etc.).

- Special measures aimed at reducing the unpaid work burden of rural households: Women and girls living in rural areas are burdened with increased care work responsibilities, due to the lack of well-established physical infrastructure in these areas. These women and girls spend more time carrying water, farming, and cooking food compared to women and girls living in urban areas. For this reason, efficient infrastructure is necessary to ease their burden.

- An alternative macroeconomic policy framework: None of the above measures can be undertaken without macroeconomic policies that will open up the space and the financial and human resources for them. Macroeconomic policies must aid job generation, allocate enough resources to create the infrastructure for social care services, invest in efficient physical infrastructure in rural areas, and allow for regulations to ensure that all these pillars are in effect.

There is a current lack of provisions and services for care work, or what Professor İlkkaracan terms ‘the care crisis’. This has resulted in a heightened and largely unregulated international migration of domestic workers to undertake these care responsibilities, resulting in multi-layered inequalities and various forms of human rights violations. The four-pillar approach may help to reduce the reliance on international migration of domestic workers, and the human rights violations related to it.

In many developing countries, we see investment in infrastructure and construction to support the growth of economies. These investments are supposed to result in job creation and keeping the economy dynamic. However, we can observe throughout the world that these investments also mean taking budget away from social services and care services, and redirecting these resources towards construction. Research undertaken by feminist scholars, including Prof. İpek İlkkaracan, challenges this notion that investment in construction provides larger returns for the economy. Prof. İlkkaracan’s research in 2015 found that for Turkey, investment into social care services has produced much further indirect jobs plus many more jobs for women, compared to investment in construction and cash transfers.

A 2019 ILO publication on research undertaken by Prof. İlkkaracan and Prof. Kim found that investment into social and healthcare areas (those under SDG targets 3, 4, 5 and 8) will directly create more jobs by 2030, as well as more indirect jobs compared to the status quo. Moreover, these measures especially support the labour force participation of women with young children, and thus support poverty reduction within this demographic.

Academic research especially from the Global South that is aimed at highlighting overlooked aspects of the impacts of macroeconomic policies on women and girls (and working on alternative scenarios) can also be used as impactful advocacy tools by civil society organisations and movements.

Gender budgeting

Gender budgeting  The COVID-19 pandemic, macroeconomy and women

The COVID-19 pandemic, macroeconomy and women

Footnotes

- 1As we have discussed and illustrated in the previous sections of this starter kit, care work for families, communities, and the natural world (which is largely undertaken by women due to stereotypical gender roles) is essential to our wellbeing and continuity of life as we know it on this planet. However, the current dominant economic structures and approaches rely on the devaluation of care, as well as a general undervaluation of work typically performed by women. These patterns of devaluation enable the economy to continue in its exploitative state. A good resource that explains these is WomanKind’s Working Towards a Feminist Just Economy: https://world-psi.org/uncsw/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ working-towards-a-just-feminist-economy-final-web.pdf